The other thing they have in common, of course, is

Alex Gibney, who has made movies about all those subjects, including the Oscar-winner

“Taxi to the Dark Side,” the box-office breakthrough

“Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” and

“Gonzo: The Life and Work of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson,” which wasn’t a big hit but strikes me as a key work in understanding what Gibney is up to. He thrives on those oversize emotions mentioned above, channeling them into intentionally ambiguous pop documentaries that inhabit a nuanced middle ground between journalism and entertainment. As he would be the first to admit, Gibney’s films depend on the work of old-school investigative journalists, those lumbering sauropods who take months or years to reach their destinations. His particular genius lies in taking their facts and figures, their reams of insider testimony, and spinning them into compelling on-screen yarns, loaded with archival news footage, goofy animations and special effects, dramatic re-creations and comic-relief moments. Yet if Gibney’s films are a long way from the purist cinema-vérité documentary tradition, they’re closer in spirit to old-fashioned muckraking than to the clown-prince pranksterism of Michael Moore. (Gibney’s voice can be heard in his films, both literally and figuratively, but he never appears as a character.) Even by Gibney’s prolific standards, 2010 is shaping up as a bonanza, or perhaps an unmanageable pileup. When I met him recently at the New York offices of Magnolia Pictures, we were officially talking about his explosive, hilarious and eye-opening Abramoff film,

“Casino Jack and the United States of Money,” which Magnolia releases in theaters this week. But Gibney also had — count ‘em —

three other new movies premiering in the Tribeca Film Festival, at least if you count his section of the anthology documentary “Freakonomics,” adapted from Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt’s bestselling books. (Other co-directors of that film are Seth Gordon, Eugene Jarecki, Morgan Spurlock and the “Jesus Camp” duo, Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady.) Gibney also unveiled a sneak preview of his as-yet-untitled Eliot Spitzer documentary at Tribeca, along with

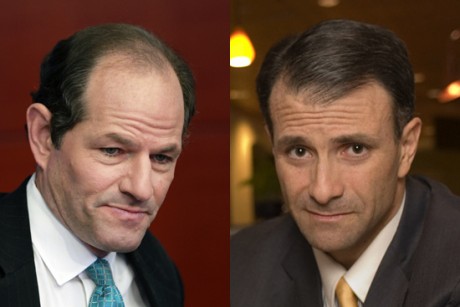

“My Trip to Al-Qaeda,” a film based on journalist and author Lawrence Wright’s solo theater piece about his quest to find the roots of Islamic terrorism. (That film will play on HBO, and perhaps also receive limited theatrical release. The commercial fate of the Spitzer film remains undecided.) “Casino Jack” veritably revels in the rollicking, stranger-than-fiction details of the Abramoff scandal, in which a brilliant and charismatic lobbyist pimped out much of the United States Congress to big-money corporate clients, along the way defrauding Indian tribes, the territorial government of the Mariana Islands and other easy marks. Beyond that, though, Gibney is fascinated by the scandal’s larger implications — and it’s there that we begin to see the conceptual thread that ties his films together. Abramoff was no rogue out to enrich himself (although he did that too) but a committed right-wing ideologue who permanently changed the rules of the game in Washington. He embraced and embodied that old gag about the Golden Rule: Those who have the gold make the rules. As always, Gibney was a cheerful, upbeat conversationalist in person. He’s a film buff who stays busy at festivals catching other people’s work, and in an interview context he delivers concise, on-message sound bites, not dark, philosophical jeremiads. Still, as I told him, I sense a pattern here, whether or not it’s entirely conscious: Gibney is documenting the not-so-slow and not-so-gradual demolition of the American dream, the interlinked vision of freedom, democracy and capitalism that has been so influential in the recent history of the world, and now seems to be in potentially terminal decay.

So, Alex, we’re here to talk about “Casino Jack and the United States of Money,” but you’ve got two other films that are either complete or almost complete. And then there’s “Freakonomics,” which you directed part of. I think you should write some kind of self-help book on how to get stuff done. Are you one of those people who’s incredibly organized? Man, that would make everybody who knows me howl with laughter. I may be the world’s most disorganized person. But I do put in the hours. I should probably join Filmmakers Anonymous. Stop me before I say yes again!

You know, you could look at your films and describe them as miscellaneous. Generally you’re taking the work of journalists and adapting it for the screen. But when I look at them, I see a congressional corruption scandal, a major corporate scandal, a disgraced politician and a dead journalist who spent his life excoriating the stupidity and corruption he saw around him. Is there a pattern? Maybe if you see it, you’ll let me know. [Laughter.] There are clearly certain things that interest me, and I seem to go there. But a pattern? I don’t know.

Well, if I were a graduate student trying to write a thesis about you, I might suggest that these are all aspects of the decline of America since 1980 — the legacy of the Reagan revolution and the triumph of conservatism in American politics. Well, there’s a theme in that. I think that’s the big story. Now we’re seeing that the net result of the Reagan revolution was the Wall Street meltdown. Take away all the rules and regulations, and what do you get? Meltdown. So I think that’s a theme. But the other thing that’s increasingly interesting for me is human behavior. What makes people do the strange things they do? How do good people go bad? How do people abuse power? Those are big things for me.

You’re showing your movie about Eliot Spitzer at Tribeca, but it has no title yet and we’ve all been asked not to write about it. So I take it you don’t think it’s ready to roll? I’m taking my cue on the Spitzer film from what happened with “Casino Jack” at Sundance. We thought it was finished. But seeing it with an audience, who weren’t my friends or anything, you learn things about how it plays. So we made it a lot shorter, we took at some narration, we just shifted stuff around. I would say the Spitzer film is largely finished, and now we’ll see how people respond. We may make a few adjustments.

Your other new film is “My Trip to Al-Qaeda,” which — well, how would you describe it? Is it an adaptation of Lawrence Wright’s performance piece? Yeah, in some ways it is. He did a one-man play called “My Trip to Al-Qaeda,” which is like “my summer vacation,” except in the Middle East. What intrigued me was that it was an everyman’s look at al-Qaida — why they attacked us, and why they came to be what they were. In making the film, we filmed the play, but then we enhanced it. The set of the play was Larry’s study, but it also included a TV screen. We made that TV screen significantly bigger on our set, and used it as a magic portal. There’s a kind of time and space travel in the film, where we go to Cairo, to London. We also travel through space and time to the caves in Afghanistan, to Saudi Arabia, so that you can see and feel these places in addition to traveling on Larry’s personal journey, which is his play.

Getting back to “Casino Jack,” which is a movie about a scandal that was widely covered in the media when the story broke, five or six years ago. It seems as if you’re arguing that people may know Abramoff’s name, and maybe the general outlines of the story, but may not understand its importance. In some ways, he assembled the tool kit that lobbyists are still using. Now, people will object to that: “Absolutely not! Jack Abramoff was one of a kind! He was completely outrageous.” Well, yes. He was outrageous, and he was way out of control. But he used the same tool kit everybody uses today: the rapacious use of not-for-profits to hide trips, to hide agendas, to hide money flows. The revolving door, where you get staffers from senators’ or congressmen’s offices and put them into your lobbying shops so you can influence votes, influence legislation. The use of entertainment and skyboxes — there are different rules now, but there are also ways to get around them. Biggest of all is the way you manage money to influence legislation, in a way that skirts the prohibitions on quid pro quo. It’s about going inside the kitchen in the world’s biggest restaurant and seeing how the sausage is made. Jack Abramoff was the master chef in the world’s biggest restaurant. We wonder why Congress is dysfunctional, why they’re not doing the people’s bidding, why everyone seems to hate them. The reason is, the system is broken, because it’s all based on money. By looking at Jack’s story, you can see how that happened. And Jack’s story — first of all, it’s hilarious and spectacular. It’s globe-girdling, there’s a murder in it, there are sweatshops in Saipan, dirty deals in Russia, arms whistling to the West Bank. But at its heart is the very stuff that is breaking our system of democracy.

This was the biggest congressional corruption scandal ever, at least at the time. But did the level of corruption that Abramoff represented become the new normal, in a sense? Because in the film you suggest that even more dramatic stuff has happened since his downfall. The dispiriting thing is that Jack Abramoff, in the wake of the financial lobbying of the last few years, looks like a piker. I mean, he’s Podunk! The financial lobbyists, and the medical and pharmaceutical lobbyists, have taken what Abramoff did to a new level.

You mentioned the fact that the Abramoff story is highly entertaining, which it certainly is. And while it’s unlikely that your viewers will find him likable or sympathetic, let’s just say this: He makes one hell of a lead character. There is another film, which is still called “Casino Jack.” I think they’re going to change the title. It’s a fictional version of this story, in which Kevin Spacey plays Jack Abramoff. I’ve seen the film, and Kevin Spacey is very good in it. But he’s no Jack Abramoff. [Laughter.] Jack Abramoff is one of a kind. As Neal Volz, a former staffer for congressman Bob Ney who later worked for Jack, says, “Jack could talk a dog off a meat truck.” He was that persuasive. He was the ultimate salesman, but he was also a man of great imagination. He was a film buff, who saw his own life as an action film or a spy thriller. As a result, he imagined himself into situations that, you know, make for pretty good moviegoing. Suddenly, we’re in Angola, in Africa, where Jack is holding a sort of

right-wing Woodstock [in June 1985], shooting machine guns with a bloodthirsty character named Jonas Savimbi and a guy named Adolfo Calero, who used to run the Contras in Nicaragua. And they’re all holding hands after a lot of machine-gun shooting and singing a version of “Kumbaya” with this guy Lew Lehrman, who later ran for governor in New York state, and who gave George Washington’s bowl to Jonas Savimbi, this bloodthirsty dictator. You can’t make this stuff up!

Yeah, I literally couldn’t believe that entire sequence. It’s so amazing. It seems impossible, totally fictional. Was it difficult to find documentation of that event? It sure was. We got lucky or we were good, one of the two. We tracked down a cameraman who had been there, and he still had 10 hours of footage. We also got Jack’s film, which was amazing. Jack was a film producer. He produced

“Red Scorpion,” with Dolph Lundgren [released in 1989], and “Red Scorpion 2.” I think the Angola affair — it taught Jack that it wasn’t a big enough deal. That was his documentary version, and he was always going to make an action film. So he reinvents Savimbi into Red Scorpion, and has Dolph Lundgren as the action hero, shooting up everybody and performing weightlifting tricks. And that’s what Jack was as a young man, a weightlifter. So Dolph Lundgren is standing in for Jack. I have a fun thing at the beginning of the film. There’s this thing that Jack

said to somebody, which we transposed into an e-mail: “Documentary? You don’t want to make a documentary. Nobody watches documentaries. You want to make an action film.” So to some extent, this film is an action film. That’s what I told Jack: “It’s an action film, man. People are going to be entertained.” I think it’s also a comedy, at least in parts. But unfortunately it’s a comedy in which the joke’s on us.

So you’ve had contact with Abramoff. What was that like? Very interesting. I visited him in prison, and found him to be a very engaging character, very funny, good storyteller. He loves to quote movies.

Did he know who you were? He did. I think — no, I know — that there was great reluctance to meeting with me. It wasn’t like I had a big record as a movement conservative, which was something we joked about. We agreed on one thing: I didn’t see him as a bad apple. I saw him as spectacular evidence of a rotten barrel. He was at the center of things, not on the periphery. Everybody else was trying to make him the scapegoat: “Oh, we got rid of Jack Abramoff. Everything’s fine!” I told him, and I firmly believe, that he was at the center. He was doing stuff to the extreme, yes, over the top. But he was doing the same stuff everybody else was doing.

Well, you make a pretty strong case that Abramoff wasn’t in it for the money, or not entirely. He had an ideological motivation. He actually believed he was doing the right thing. Right. I think he was a zealot. Unlike his partner, Mike Scanlon, who was in it for the money, Jack Abramoff was a zealot. He believed in the principles of the Reagan revolution. He was very anti-Soviet, but he also wanted to do what Grover Norquist has suggested: make government so small you can drown it in the bathtub. Denude it of its resources. Destroy the government, in effect.

Do you see any parallels between Abramoff and Eliot Spitzer? Here are these two brilliant, headstrong guys from opposite sides of the political spectrum, who appeared to be very idealistic, driven by ideology, but who allowed themselves to become corrupted. I don’t know that Eliot was corrupted by his ideology, but I think he’s a character who did something that was wildly unexpected. If there is a parallel, it’s hubris. I think Jack became so entranced with his outsize reputation that he began to believe his own press releases. And I think Eliot Spitzer — he started seeing prostitutes at the moment of his greatest political influence. He was on his way to being governor, overwhelmingly popular among both Republicans and Democrats. And at that very moment, at the top of his game, he began to see prostitutes. Dudley Do-Right did wrong.

Of the two of them, maybe Spitzer was the real hypocrite. You can call Abramoff a lot of things, but not that. I don’t think you could really accuse Jack of being a hypocrite. Jack was corrupt, and I don’t think you can say that Eliot Spitzer was corrupt. But he was hypocritical, there’s no doubt about that. Look, he had increased penalties for johns in New York, and he had prosecuted escort services. Now, I have rather politically incorrect liberal views about whether prostitution should be legal. [Laughter.] But the fact was that it was illegal, and he was the governor of New York, who had convinced people to elect him because he was Mr. Clean. So, yes, he was a hypocrite. And Jack wasn’t.

“Casino Jack and the United States of Money” opens May 7 in New York, Los Angeles and Washington; May 14 in Chicago, Phoenix, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose, Calif., Santa Cruz, Calif., and Seattle; May 21 in Atlanta, Boston, Monterey, Calif., Nashville, Palm Springs, Calif., Philadelphia, Sacramento, Tucson, Ariz., and Austin, Texas; May 28 in Charlotte, N.C., Cleveland, Dallas, Kansas City, Miami, Minneapolis, Portland, Ore., Salt Lake City, San Antonio and Santa Fe, N.M.; and June 4 in Houston and Waterville, Maine, with more cities to follow.

No comments:

Post a Comment